Common menu bar links

Canadian statistics in 1914

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

The Department of Agriculture had been officially responsible for handling Canada’s statistics since Confederation, but by 1912 the dynamic and industrial character of the country had changed. On April 1, 1912, the Census and Statistics Office was transferred to the Department of Trade and Commerce, under the direction of Minister George Eulas Foster.

In a matter of weeks, a Departmental Commission on Official Statistics, or the Foster Commission, was formed. On May 30, 1912, this commission was instructed “to inquire into the statistical work now being carried on in the various Departments, as to its scope, methods, reliability, whether and to what extent duplication occurs; and to report to the Minister of Trade and Commerce a comprehensive system of general statistics adequate to the necessities of the country and in keeping with the demands of the time.”

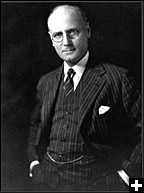

Members of the commission included Ernest H. Godfrey of the Census and Statistics Office and Robert Hamilton Coats—a young journalist, statistician and associate editor of the Labour Gazette for the Department of Labour.

Changes to the Canada Year Book

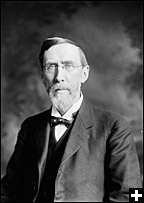

In 1912, Archibald Blue, Chief Officer of the Census and Statistics Office and editor of the Canada Year Book, conceded to what he called “a considerable number of changes and additions.” In 1913, the position of editor of the Canada Year Book passed to Ernest H. Godfrey, who reported that “progress had been made in the direction of greater comprehensiveness with a view to increased usefulness of the work for purposes of research.”

Details on vital statistics, climate and meteorology, labour, provincial revenue and expenditure, and public lands were added and articles were written about the history and physical characteristics of Canada. Also, the Canada Year Book now included bar and line graphs, pictures of historical Canadian personalities and landscapes in addition to the text.

Quite suddenly, Archibald Blue died in 1914 at the age of 74, while still Chief Officer of the Census and Statistics Office. He was replaced by Robert Hamilton Coats, who was appointed Dominion Statistician in the Department of Trade and Commerce. The title of Dominion Statistician had only been held once before—by George Johnson, the early editor of the Canada Year Book.

A population poised for war

By 1911, the country held around 7.2 million people, with the majority, 6.4 million, born in Britain, Canada or another of the ‘British possessions.’ However, the foreign-born population was growing. There were 279,392 more people from Europe (excluding the British Isles), 125,549 more people from the United States, 17,366 more people from Asia and 1,744 more people from elsewhere in Canada than there were in 1901.

Even though the foreign-born population of Canada was increasing, starting in 1908 the country actively slowed the rate of Asian immigration by passing laws that, for example, excluded “Japanese labourers from Hawaii and of Hindus from Hong Kong and Shanghai.” Another example of Canada’s strict policies were Canadian immigrations laws, which were enforced when a Japanese steamer—the Komagata Maru—carrying Hindus and Sikhs from Shanghai was turned away from Vancouver on July 23, 1914, because it was unable to meet the requirements of immigration laws.

Navigating the nation

Over one thousand people died when a thick fog caused the Canadian Pacific Railway Company’s steamship, the Empress of Ireland, to sink on May 29, 1914, when it collided with the steamer Storstad in the St. Lawrence River.

On August 3 of the same year, two submarines built in Seattle were bought by the Canadian Government and brought to the naval base at Esquimalt, British Columbia, in defence of the Pacific Coast. The War Appropriation Act, 1914, granted the sum of $50 million for the military and naval defence of the country, and Canada immediately committed to protecting its coastal waters. The Rainbow and the Niobe were positioned in the Pacific and Atlantic to guard the country’s coastlines.

Preparing for a wartime economy

By 1914, the country set up 1,217 grain stations, had 2,607 grain elevators in operation and could effectively hold 155 million bushels of grain, which was an incredibly important resource during the war.

To the gratitude of the British Government, on August 6, 1914, the Governor General of Canada, on behalf of the people of Canada offered to the British 1 million bags of flour, 4 million lbs of cheese, over 1 million tins of salmon, 100,000 bushels of potatoes, 1,500 horses and more. This offer provided the British with much-needed relief during the war.

The average yield of wheat from 1910 to 1913 was 204 million bushels; however, in 1914, wheat production fell to 161 million bushels.The price of wheat peaked in December 1914, at approximately $1.50 a bushel, whereas the price of wheat flour peaked in September at $9.20 per 280 lbs.

Our military might

Prime Minister Borden spoke of the achievements of the military training camp at Valcartier, Quebec, saying “thirty-five thousand men were assembled and put through a most systematic course of training in all branches of the service. Infantry, Cavalry, Artillery, Engineers, Army Service Corps, Army Medical Corps, Signallers and Ammunition columns were organized, and all were trained in their respective duties.”

By March 31, 1914 Canada had in its military a permanent force of 3,000 officers, non-commissioned officers and men and an active militia of 5,615 officers and 68,991 non-commissioned officers and men.