Common menu bar links

Canadian statistics in 1905

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

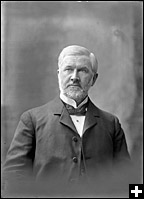

George Johnson, editor of the Canada Year Book since 1886, responded to increased international demand for the book with imagination and resourceful marketing tactics. He modified and refined the book’s content and created a simpler volume, which allowed for more copies to be published. In 1897 alone 5,500 copies were produced, up from approximately 4,000 in 1896. Nearly 10,000 copies of Johnson’s last edition of the Canada Year Book were published in 1904.

Despite Johnson’s achievements, in December 1905, Archibald Blue, the Special Census Commissioner for the Census of 1901, was appointed Chief Officer of the new, permanent Census and Statistics Office—a role that included the editorship of the Canada Year Book. At the age of 72 in 1906, George Johnson retired as Dominion Statistician—a title he had held since 1894.

Displaying the numbers

Regrettably, the Canada Year Book 1905 lost the ingenuity and flavour that Johnson had cast into it. Under Blue, the book’s priority fell behind that of other publications, like the new Census Bulletin Series. The Canada Year Book, “starting with the 1905 edition, was starker and briefer than ever before since, among other changes, it now provided only Dominion Statistics and, except for an introductory section by E. H. Godfrey recounting ‘Events of the Year,’ contained no textual matter.”

Since the book did not contain any explanatory text, the Canada Year Book 1905 was a mere collection of various tables under three large headings: “Tables compiled from census reports,” “Tables compiled from departmental reports,” and “Records of cabinet ministers, governors-general and lieutenant governors.”

Counting the population

Confederates in 1867 dreamt of a Canada with at least 12 million people by 1900, but the population grew very little and was much smaller than expected. By 1901, the country only held just over 5 million people.

At the same time as the number of women approached that of men—there were 2.6 million women and 2.8 million men in 1901—the number of people married in Canada rose from 1.6 million in 1891 to 1.8 million in 1901. The number of people widowed also increased from 1891 to 1901, by 17.3%. Both the number of families and the number of houses in the country reached nearly 1.1 million by 1901. Also, for the first time, the census in 1901 counted the number of people divorced: 661.

By 1905, the immigration campaign started by Clifford Sifton, the Minister of the Interior, had been running for several years and was attracting many people to Canada’s Prairies. In 1905 alone, 146,266 immigrants arrived at Canada’s inland and ocean ports, compared with the mere 50,000 that arrived in 1901. Immigrants came primarily from the United Kingdom, but also from other areas of Europe, the United States and Iceland.

Improving the infrastructure

During the 1905 session of Parliament, the first laws on the control of wireless telegraphy were passed in Canada. The restrictions passed stated “that no person shall establish a wireless telegraph station or install or work any apparatus in any place or on board any registered ship, except under and in accordance with a license granted by the Minister of Marine and Fisheries with the consent of the Governor in Council.”

In the Dominion of Canada in 1905, the government’s own company—Dominion Government Telegraph Service—had 338 offices in the country. The number of private and public telegraph stations in Canada was 3,162.

In 1905, the Dominion of Canada had 20,487 miles of steam railways in operation. The government began tracking the growth of the country’s new electric railways in 1901. By 1905, Canada had almost 800 miles dedicated to these electric railways—the longest being the Montréal Street Railway at 124.42 miles.

Tracking the economy

On September 1, 1905, the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta were created, opening Western Canada to settlement and agriculture. The very same day Parliament enacted the Seed Control Act, which empowered the government to fine people for introducing weeds to the Prairies, “provided that in the case of the first offence the total fine shall not exceed $5, and of the second offence $25, or imprisonment for a term not exceeding one month.” The act targeted those who sold, offered or exposed, or had in their “possession for sale for seeding any seeds of cereals, grasses, clovers or forage plants” that were mixed with weeds, including types of wild mustard, orange hawkweed, ox-eye daisy, night-flowering catchfly.

Industries in Canada began to show promise. By 1905, three sugar beet factories had been built—two in Ontario and one in Alberta—that manufactured sugar from 118,095 tons of beets at a value of $1,045,288, up from 51,067 tons and $385,678 just three years earlier.

Canada anticipated the growing industrialization of the 20th century by passing the Conciliation Act of 1900, which established the mechanisms needed to settle trade disputes by collecting informed statistics on labour conditions in the country. The Canada Year Book 1905 reported that “there were fewer industrial disputes in Canada during the year 1905 than in any of the previous years of the decade, the total number being 87 as compared with 104 in 1901, 123 in 1902, 160 in 1903 and 103 in 1904.”

Building the militia

After a half century of debate, in 1905 British troops were finally withdrawn from Canadian soil, leaving the defence of the country to Canadians. The Governor General of Canada spoke at the 1905 session of Parliament, saying “the addition to the number of the permanent force which you have authorized will enable [the British] Government to relieve the taxpayers of the United Kingdom from the burden of keeping up the garrisons of Esquimalt and Halifax.”

In 1905, the Government of Canada paid nearly $4 million to maintain the militia, which consisted of 44,200 men in authorized establishments, 37,212 men with at least 12 days of training, 2,280 men with less than 12 days of training, and 4,708 men with no training at all.